Click Center Image for Full Size Picture

More soldiers died of disease during the Civil War than were killed in battle. Intestinal disorders such as diarrhea, typhoid fever, and dysentery were rampant in the camps, along with various types of fevers, measles, chicken pox, mumps, whooping cough, and small pox. Men who left their home towns for the first time were exposed to new diseases that they had no immunities against. A lack of sanitation and close quarters contributed to the spread of disease, and poor food, lack of shelter, and a lack of proper clothing increased their severity. In the field, a common cold could quickly become pneumonia.

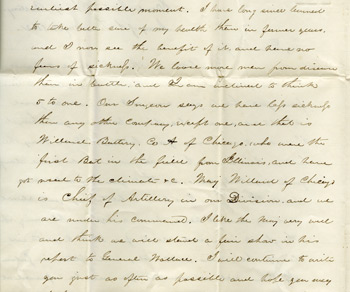

Cheney noted in his July 31, 1862, letter that the soldiers appeared to go through a "regular course of ailments" in the camp. He also noted that the men who stayed in camp while ill eventually did not get sick as often as those who went home to recover.

Medical knowledge and training were especially poor at the beginning of the war. Some medical treatments, such as bleeding and arsenic compounds, now seem worse than the diseases that they were used to treat.

Headquarters, Cheney's Battery, Army of the Tennessee.

Many men who survived their wounds suffered from infections; so called "surgical fevers" and gangrene were common occurrences. Although surgeons were aware of a connection between cleanliness and preventing infections, they did not know how to sterilize their instruments. Surgeons on the battlefield often could not wash their hands between patients because they did not have enough water.

In his letter of June 15, 1862, Cheney admitted to Mary that he was sick, but refused to see a doctor "after what I have seen of their practice." Like many other soldiers, Cheney used patent medicines and home remedies for his ailments, such as taking rhubarb to treat the "Tennessee Quick Step"—diarrhea.